DLNR Director’s Job Has Changed

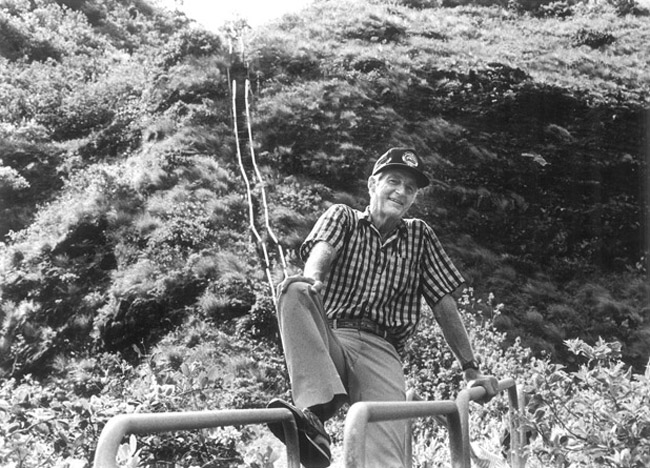

DLNR director Bill Paty pauses on his way to the top of Oahu’s Haiku Stairs in August 1988 Carl Viti / Star-Advertiser photo

Aside from the run-on sentence, state Department of Land Natural Resources’ mission statement sounds from the book of Genesis: “Enhance, protect, conserve, and manage” for generations unto infinity.

DLNR employs 900 people across the state. They license fishermen, hikers, campers and hunters. They protect reefs, guard against invasive species, maintain parks, define historic districts — the list goes on. But, most important, they manage state lands.

The state Senate decided that Carleton Ching’s qualities were insufficient to these many tasks, that his employment with a land developer crippled him.

Says one former DLNR employee: “For its first 50 years, DLNR’s task was to develop land and water for development. We’re past that. The role of the modern era DLNR’s is stewardship of land and water.

“A lot of passionate people look to DLNR; people for fishing in an area, people opposed to fishing in the same area, people for development, people opposed to it. Some have short-term, self-interested motives.”

Dealing with absolutists hasn’t been easy for either the department or the people who’ve led it. No modern DLNR chair has survived more than one term since Bill Paty. Gov. John Waihee appointed him to the post in 1986; Paty left the job in 1994 at the end of Waihee’s second term.

Paty is a tough guy. As a captain in the 101st Airborne Division, he parachuted into Normandy on June 6, 1944. The Germans captured him; he attempted to escape three times. He ran Wailua Sugar Company. He chaired Hawaii’s 1978 Constitutional Convention. Paty doesn’t shy away from jobs both monumental and varied.

“It may be the hardest job in the state,” says Robert Harris, former executive director of Sierra Club Hawaii. “The chair has to say yes to the good and no to the bad. His job extends from development to conservation, and he has to persuade representatives of both to buy into his decision.”

Paty expressed similar sentiments in a 2011 interview with PBS-Hawaii: “With land and water, and all the natural resources, it was a great, grand, frustrating job. But we were fortunate, for the most part, we had money. I feel that today it’s a tough ticket when you don’t have the funding that’s needed to improve and maintain our natural resources.”

Dolores Foley, chairwoman of University of Hawaii’s Department of Urban and Regional Planning, agrees: “DLNR is way underfunded. They don’t have anywhere near enough money to reach the goals they’re mandated to achieve.”

So what’s to be done if there’s not enough funding or if immovable forces collide?

Paty again: “At some point, you just gotta say, ‘Hey, we’ve given this our best thought, and we’ve put much concern into it, but we have to make a decision, and much as I don’t like it, we have to agree to disagree.’ Then move on.”

So, if not Ching, who?

All agree it should be a good communicator with knowledge of DLNR’s varied roles. Foley would bring back Bill Aila, Gov. Abercrombie’s appointee; Harris mentions Matthew Fox of The Nature Conservancy,

Lea Hong of The Trust for Public Land, Josh Stanbro of Hawaii Community Foundation or Aulani Wilhelm of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

How about a certain someone straight out of the book of Genesis?

dbboylan70@gmail.com