Digesting A Bad Dining Experience

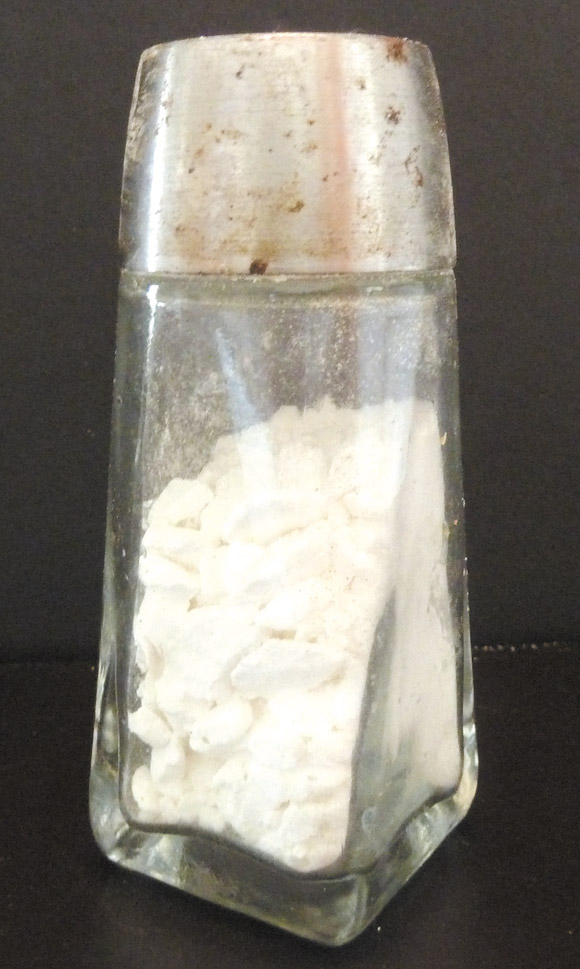

The author was faced with choosing to get salty or letting it flow better for the next customer | Jane Esaki photo

I ask for an ocean view, but the young hostess puts the place setting so it faces an adjacent table instead of the readily available view. The server finally takes our order 15 minutes after we ask for a couple of minutes. The bacon burger arrives … without the bacon. The grilled fish is overcooked, tough and tasteless. Finally the salt that is supposed to save the fish won’t pour at all from the shaker.

This comedy of errors is not funny — it’s enough for me to complain and send the food back to the chef. But my shikata ga nai (it cannot be helped) mom dining next to me won’t have that. “Don’t say anything,” (don’t embarrass me), she knowingly whispers to me in Japanese, just as I’m already vigorously assessing the situation and devising a strategy to overcome the emotionally devastating slight.

OK then, Mom. I try hard to come up with reasons why I should comply with her wishes because she is the elder, and they always know better.

So I begin rationalizing. These are young kids who are serving us, making minimum wage and still learning the ropes. The cook is having an off day. The burger is moist and flavorful, and anyway, we don’t need the bacon’s extra crunchy delicious saturated fat. The green salad is fresh and crispy as it sits next to the fish. Conspiracy theorists would applaud me for limiting my mercury and radiation intake in one sitting anyway. Plus I can doggy bag it and make fish stock for miso soup later.

This is as close to Zen as I can get. But as we finish our meals, apparently I am not enlightened enough. This rationale just isn’t enough for me to bite my tongue because, hey, these things can be helped.

The staff needs to know, so future customers are happy and the restaurant stays successful, so it can stick around to add to the mix of dining choices on Kauai and keep its workers employed.

Then, a bizarre thought arises.

Sure, they need to know, but they don’t need to know in a negative way. They don’t want to hear me complain. And they would rather not get yelled at, rack up more time to complete the burger, or lose money on the fish.

And guess what? Other diners might beg to differ, but I would prefer not to complain loudly, stay a minute longer, or waste the precious fish either.

When the waiter comes to grab our plates without first asking how the meals were, it is my cue. Holding my composure, I stoically explain the major mistakes to the waiter but beg that he not worry about it. I only ask that everyone knows so they can better serve future diners. He apologizes sincerely and returns with the bill minus a small token discount. We still give them a big fat tip, for which the waiter and hostess appear grateful. As we walk out, everyone is still smiling.

Including my mom, which is all that matters in the whole scheme of things.

janeeskai@gmail.com