150 Years Later

Koa Gomes with his son, Duke, and his mother, Keone Cook

2018 marks the 150th anniversary of the first Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, The Gannenmon. Their descendants continue to shape the future of the state today.

The year was 1868. Japan had only just settled the question of the Meiji Restoration: a tumultuous period that saw the Tokugawa shogunate — which had ruled Japan for more than 150 years — dismantled by force. The imperial family retook control of the country. Western modernization became the rule of the day, changing the course of Japan’s history.

Across the ocean, in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, the young Kamehameha V had rewritten his country’s constitution, returning power to the throne. The economy was booming, but the burgeoning sugar industry needed a fresh source of laborers.

Several years before, Hawai‘i foreign affairs minister Robert C. Wyllie had sent Eugene Van Reed, an American businessman, as an envoy to Japan to seek fresh blood. Van Reed quickly found that the timing was, perhaps, not ideal.

With Japan in turmoil, Van Reed managed to gather a motley crew of approximately 150 in the port town of Yokohama to board the Scioto, a British vessel, to return to Hawai‘i as plantation laborers.

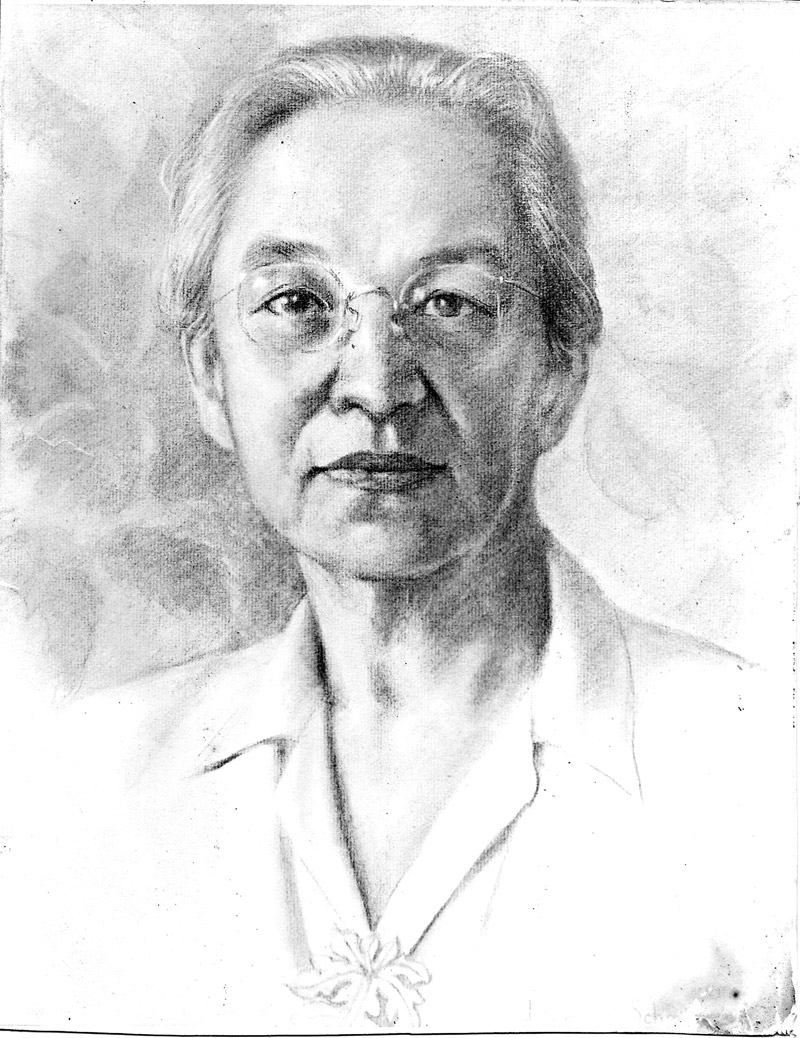

Kimi Matsu Cook, daughter of Matsugoro Kuwata, aka ‘Umi’umi Matsu.

He had secured the necessary permits and permissions from the shogunate, but, of course, by the time departure rolled around on May 17, 1868, the shogunate was no more.

So he and his laborers fled without permission from the Meiji government, headlong into an unknown future in Hawai‘i.

They were the Gannenmono, the first Japanese immigrants in Hawai‘i, the “first year people” — so named because 1868 was the first year of Emperor Meiji’s reign. 2018 marks the 150th anniversary of their arrival.

One of the men aboard that ship was named Matsugoro Kuwata.

This is his family’s story — and Hawai‘i’s, too.

Koa Gomes is Kuwata’s great-great grandson. He admits that he wasn’t fully aware of his family history until he began learning more in the last few years.

“At that time that the Gannenmono came, it was when a lot of samurai were leaving Japan, and I thought, OK, cool, I am part-samurai, and I did a lot of research on it — and it turns out he was a tailor, which was very cool, but it’s not a samurai,” he says with a laugh.

Kuwata was born in 1839 in Oyama, Kanagawa. As he was a tailor by trade, his descendants do not know why he chose to test his fortunes in Hawai‘i as a farm laborer.

“I assume it was a chance for a better life,” says Keone Cook, Kuwata’s great-granddaughter (and Gomes’ mother).

Kuwata was hardly the only Gannenmono ill suited for a laborer’s life in Hawai‘i. The band of 150 included a number of ex-samurai, merchants and other city dwellers — not farmers. They were distressed by the long hours, heavy labor and low pay.

Kuwata (far left, seated) with his family, including his six children (Kimi is standing on the far right) and his wife, Meleana (seated, with baby). PHOTOS COURTESY KOA GOMES

Complaints from the Gannenmono triggered an investigation from Japan, which ultimately would discourage further Japanese immigration for the next 20 years, until the hundreds of thousands of laborers known as the Issei began arriving in the 1880s.

Some of the original 150 even went home right away, rather than go on. But Kuwata stuck out his contract at Ha‘ikū Planation on Maui. And instead of returning home or moving to the Mainland, he stayed.

He changed his name, first of all — he became ‘Umi‘umi Matsu, adopting a Hawaiian nickname bestowed on him for his famous beard. He also married a Hawaiian woman, Meleana Auwekoolani, herself an accomplished quilt maker, in Makawao.

“He returned to his trade after his two years were up on Maui. He moved to Hilo and opened a retail tailor shop right on Kamehameha Avenue,” Cook says.

He had six children, including Kimi Matsu, who sewed quilts like her mother and worked as a teacher and eventually principal at Hilo Union School.

“She would wear these big, loose mu‘umu‘u, even when they went swimming, which was funny,” remembers Cook of her grandmother. “For little snacks she’d have little dried fishes; I remember little dried manini in her pockets. She was kind of quiet, soft-spoken.”

Kimi Matsu wed Thomas Cook of Moloka‘i, a land surveyor. They had five children.

One of those children was also a Thomas Cook, a banker who eventually became chairman of Hawai‘i

County Board of Supervisors — the precursor to the mayor’s office.

Among many achievements, like establishing a sister-city relationship with Oshima, Japan, Thomas Cook was responsible for rebuilding and moving Hilo several miles inland after the devastating 1960 tsunami.

Some of the coconut trees planted as shorebreaks during that time still exist along Hilo Bay.

“I remember him taking me around to see the devastation of the tidal wave,” Cook says.

Thomas Cook also was, of course, Keone Cook’s father. He married May Kaenaokalani Bradley, and had five daughters.

Cook, who won the Miss Hawai‘i competition in 1980, spent more than 30 years in cosmetics before switching to a career in real estate with Berkshire Hathaway. She has three sons, including, of course, Koa, a branch manager at Central Pacific Bank, who is himself father of Duke Gomes, 3, with wife Kara (née Sugimoto).

Duke, therefore, is a great-great-great grandchild of ‘Umi‘umi Matsu — 150 years later, his bloodline continues.

How has this illustrious heritage affected the family?

“I think it’s different because we do not look Japanese,” Gomes says. “My son is blond. I think it’s a much different experience for us.”

Cook, after all, has Japanese, Hawaiian, Chinese, Irish and English blood in her veins — and Gomes has all that plus Portuguese.

Rather, the legacy of Matsugoro Kuwata has been one of resilience and cultural embrace — the kind of success story that embodies the best of Hawai‘i.

“Our homes were so multiethnic, and we were exposed to so many different cultural practices,” Cook says.

“You don’t realize how it all seeps in,” Gomes adds. “For kids that grow up in Hawai‘i, you grow up using chopsticks, all kids know how to measure rice without a measuring cup, nobody wears shoes in the house, everybody wears rubber slippers — it’s all around.

“We had no idea how much of a part of our DNA it was until we got older.”

Gomes hopes he can teach his son how to embrace his roots and treasure the different heritages that flow through his veins — just as Kuwata embraced his new home and people, 150 years ago.

“Maybe he won’t realize it until he goes away to school on the Mainland, but I think that it’s a very unique and special thing just to come from so many different places in the world … to be the true embodiment of the melting pot.”